There’s a reason why cocaine sits high on the list of the world’s most popular recreational drugs. Like cannabis and alcohol, the two other reigning champions, coke is abundant and easy to procure, its effects are quick and intense but not overbearing, and it makes social gatherings and events more uninhibited and enjoyable.

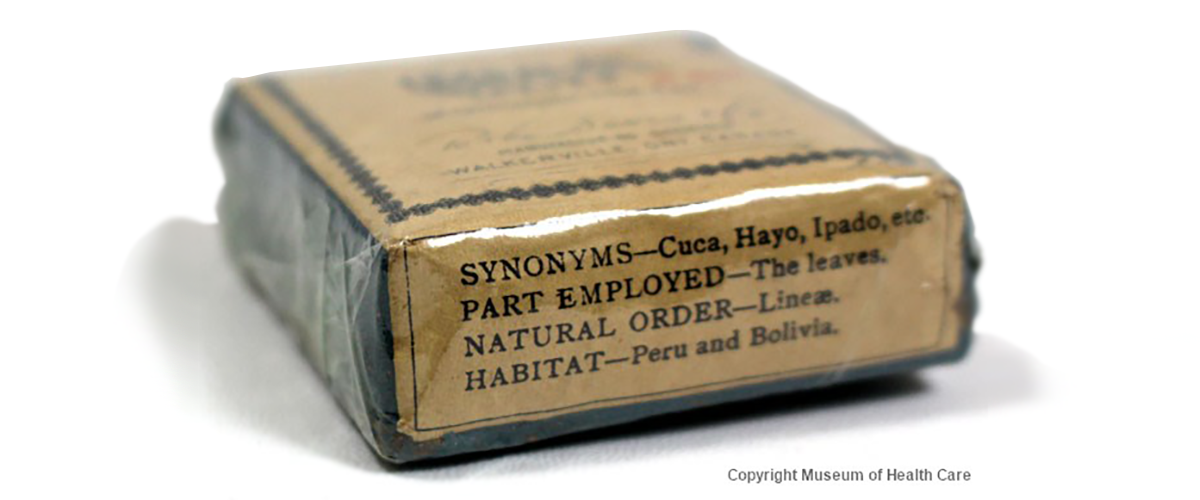

Once scientists figured out how to extract it from the coca plant, which had been used traditionally by South American indigenous people for hundreds, if not thousands of years, the Western world wholeheartedly embraced the ‘power powder’ as a perfect tool for enhancing pleasure and productivity.

For a while, cocaine use was a fully legal symbol of affluence; its effects echoing the unbridled progress of civilization at the time. Buildings were popping up, business was booming, and blow was sniffed in celebration of success and abundance.

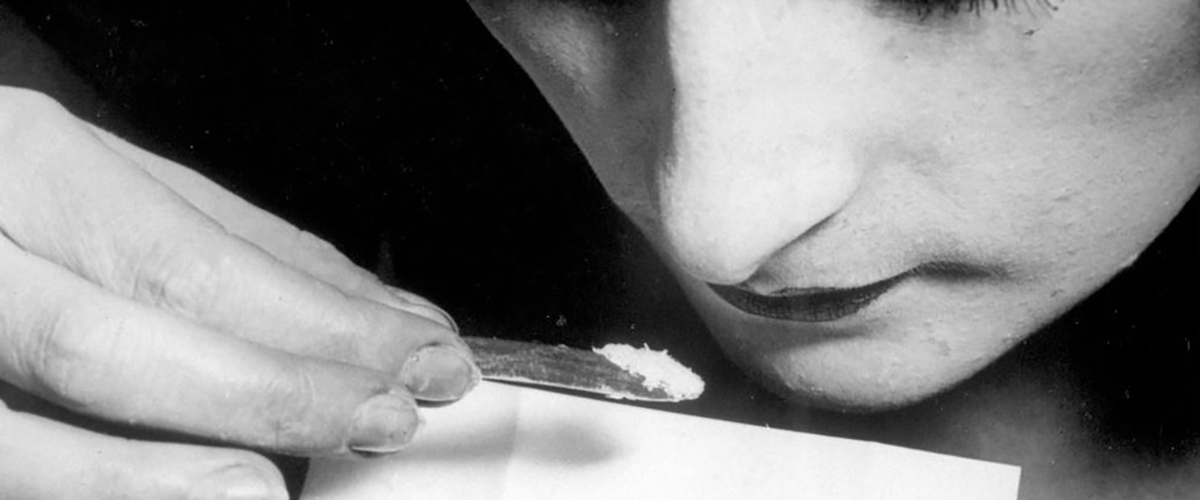

However, as most experienced powder lovers know, cocaine takes a lot of willpower to consume with moderation; one line leads to another, and soon the crystal cookie crumbles. Just as it is on an individual level, so the collective cocaine abuse brought the West to its knees in the 20th century.

Today, we know better, and cocaine is by and large used with less regularity, as a recreational substance at events and parties.

So, without further ado, let’s run through cocaine’s fascinating journey throughout history and learn how it got from the Andean highlands to the bathroom stalls in bars and nightclubs across the world.

Cocaine has a long history of traditional use among South American indigenous people. The remains of leaves of the plant Erythroxylon coca were unearthed in excavations of over a thousand-year-old Peruvian ruins.

It’s assumed that these ancient people were chewing on this plant, commonly known just as ‘coca,’ for multiple purposes: to increase their energy and stave off hunger and thirst during work, for social and religious rituals and ceremonies, and to combat the lack of oxygen at high altitudes by making their hearts beat faster and their breathing accelerate.

Even nowadays, if you travel to some Andean town or city which is high up in the mountains, you will be met by an array of coca leaf peddlers at any tourist destination. These leaves are a major lifeline in the first days of altitude sickness for any gringo visitor not used to oxygen deprivation.

The coca plant is legal in these cultures; it is viewed as a medicinal herb. Just like the West would discover centuries later, aside for its stimulating effects, it was also used as an anesthetic for painful medical interventions.

Once the Spanish missionaries arrived, they discovered that the indigenous peoples used a variety of consciousness-altering plants (the most famous one is likely ayahuasca) and labeled this whole area of early biohacking as demonic in nature. However, soon they would warm up to coca, seeing its apparent medicinal benefits and usefulness as an energy booster for their many forced laborers.

Coca did not receive much attention in the coming centuries because the long times necessary for the transport of the leaves would make them lose potency and degrade significantly, and chemistry was nowhere near the level needed for isolating and purifying the active compounds themselves.

However, history was made in 1855, when a German chemist named Friedrich Gaedcke managed to extract an alkaloid he named “erythroxyline” based on the botanical name of the plant it came from. A few years later, in 1859, another German scientist, Albert Niemann, successfully developed an improved purification process, catalyzing the birth of the cocaine we know today. So, next time you do a line, make sure you give some appreciation to this pair of relatively unknown German geniuses.

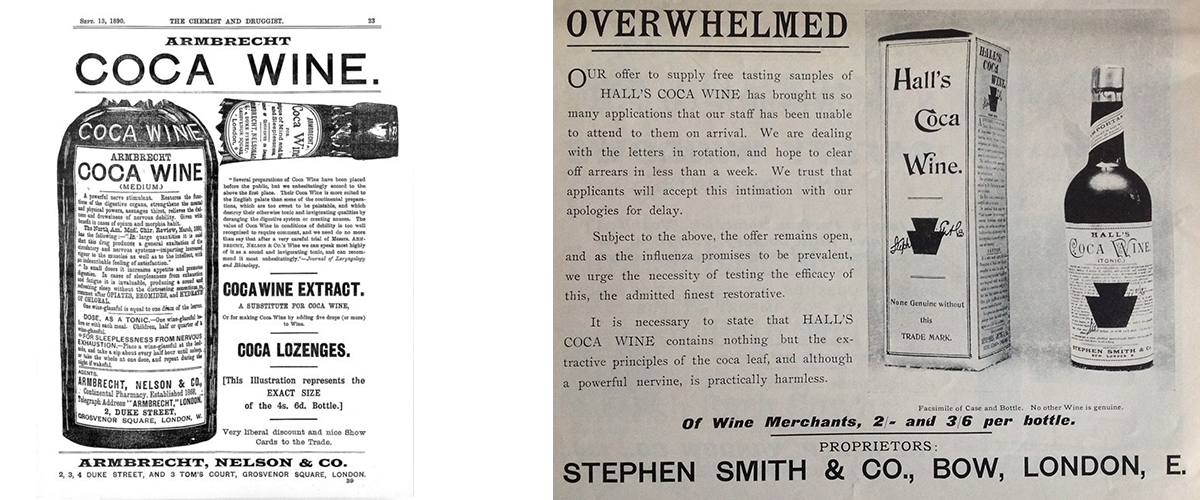

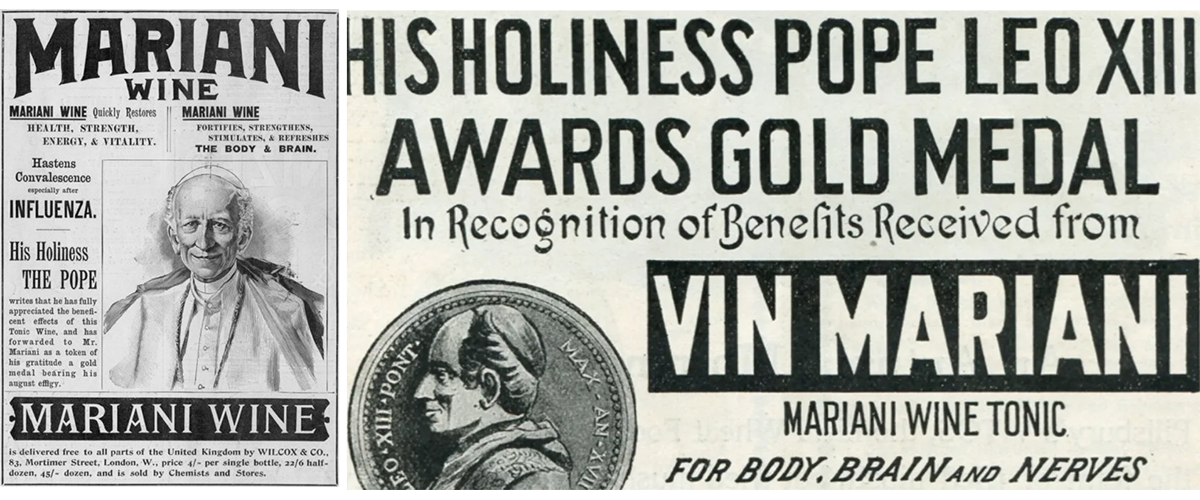

In 1863, a chemist by the name of Angelo Mariani had created a coca-infused wine—Vin Mariani—which brought cocaine into the homes of common people. The subtle addition of a cocaine high to a wine high was an instant hit, so much so that even the Pope presiding at the time, Leo XIII, appeared on a poster endorsing the wine and awarded a Vatican gold medal to Mariani for creating it.

Vin Mariani had a plethora of notable proponents from around the world, including such names as Thomas Edison, Ulysses S. Grant, Jules Verne, Alexander Dumas, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Émile Zola. Its low concentrations of cocaine made it perfectly safe to consume and it remains to this day the least harmless popular cocaine product ever made. Mariani never passed on the recipe of his drink to his family members, and the wine’s production ceased after his death.

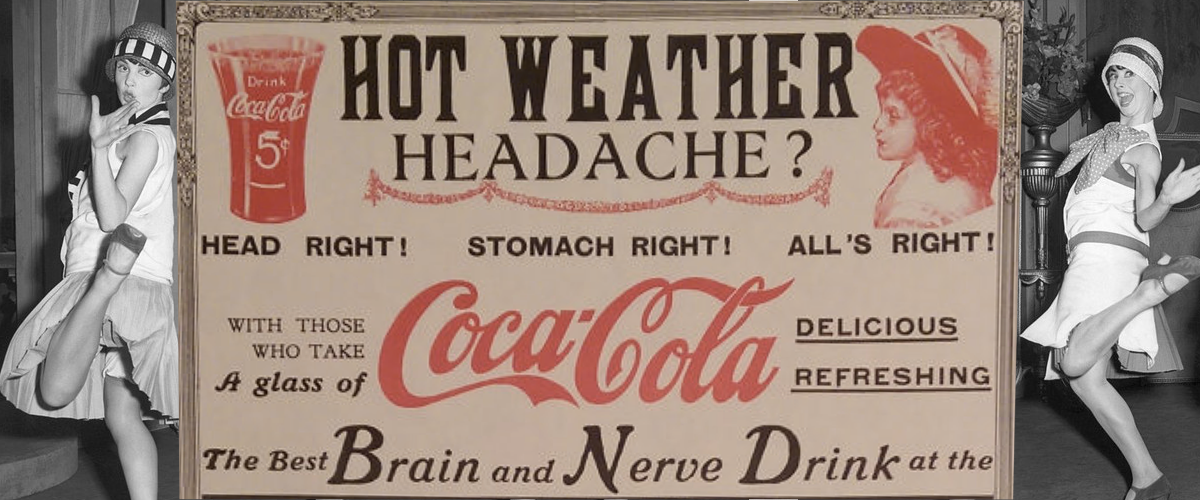

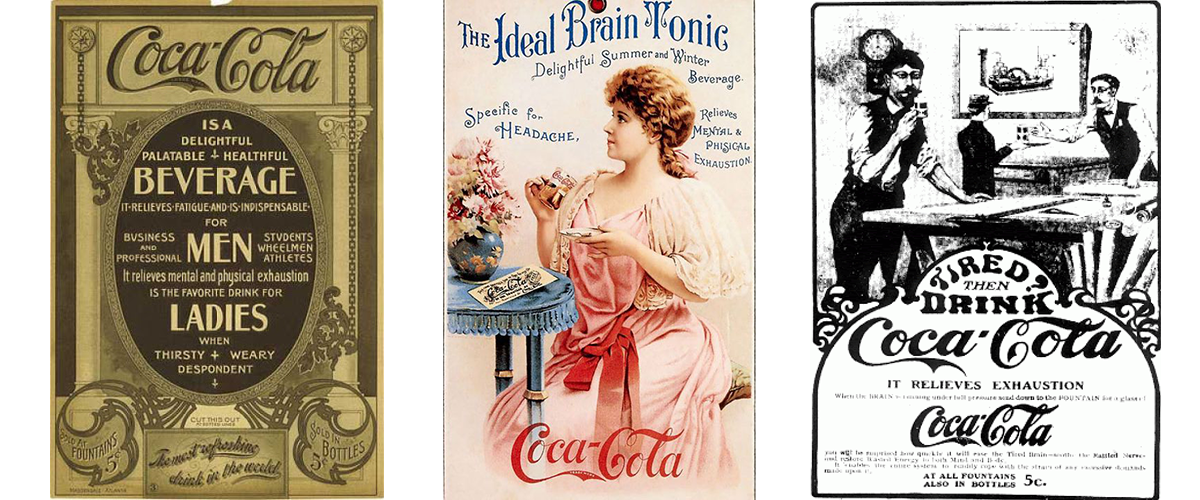

Two decades after the popularization of Vin Mariani, American biochemist John Styth Pemberton drew on the inspiration and came up with his own recipe. The original ingredients included cocaethylene (cocaine mixed with alcohol), kola nut (the fruit of the African Cola tree), and damiana (a Mexican shrub commonly used as an aphrodisiac and for a variety of other therapeutic purposes).

The concoction, which he named ‘Pemberton's French Wine Coca,’ was touted as a panacea of sorts, claimed to heal a wide range of stress-related diseases including nerve trouble, dyspepsia, gastroparesis, mental and physical exhaustion, gastric irritability, wasting diseases, constipation, headache, neurasthenia and impotence. It was marketed mostly to upper-class intellectuals, such as “scientists, scholars, poets, divines, lawyers, physicians, and others devoted to extreme mental exertion.”

The original recipe was short-lived, lasting only a few years before alcohol prohibition forced Pembleton to tweak it in order to comply with the law, creating the early version of what we now know as Coca-Cola. Ultimately, in 1903, cocaine was removed from the recipe due to the social stigma that had started developing toward the powder. Decocainized coca leaves remain an ingredient of Coca-Cola.

The use of cocaine itself ramped up thanks in part to another famous powder proponent—Sigmund Freud. The influential clinical psychologist, whose theories on the subconscious mind were eventually leveraged by his nephew Edward Bernays as the foundation for modern-day public relations and marketing, had a cocaine habit of his own and did not spare praise for the magic substance.

In fact, Freud published an article in 1884 titled 'Über Coca' (About Coca), in which he detailed the history and medicinal properties of coca and cocaine hydrochloride. Using himself as the experimental subject, Freud consumed a significant amount of cocaine over several months as he recorded the drug's physiological effects and potential therapeutic uses.

Freud wrote that the effect of cocaine on the psyche includes: “Exhilaration and lasting euphoria”, which in no way differs from the normal euphoria of the healthy person. You perceive an increase of self-control and possess more vitality and capacity for work. In other words, you are simply normal, and it is soon hard to believe you are under the influence of any drug. Long intensive physical work is performed without any fatigue. This result is enjoyed without any of the unpleasant after-effects that follow exhilaration brought about by alcoholic beverages. No craving for the further use of cocaine appears after the first, or even after repeated taking of the drug.” He also noted that “For humans, the toxic dose (of cocaine) is very high, and there seems to be no lethal dose.”

Ironically, it seems that Freud, whose daughter would eventually introduce projection into the vocabulary of psychology, was just projecting his own desires on how cocaine really works.

Due to regular, excessive use of the powder, Freud became seriously addicted to cocaine, a habit which took him twelve years to kick. Meanwhile, a friend and patient of his, whose morphine addiction he attempted to cure with cocaine, ended up adding coke to his addictions and died seven years later at age 45.

A few months after Freud’s paper on cocaine came out, his close associate, Karl Koller, discovered the anesthetic application of cocaine. He conducted experiments on himself by applying a cocaine solution to his eye and then poking it with pins.

After Koller’s findings were published, cohorts of doctors were running studies left and right demonstrating cocaine’s analgesic and anesthetic properties. The medical community found them far superior to ether and chloroform, the use of which had been standard practice, albeit plagued with numerous adverse side effects. This qualified the compound for numerous kinds of surgery which had previously been very difficult to pull off.

While anesthesiologists were busy discovering cocaine’s sedating properties, its stimulating effects started garnering attention from another kind of scientists, who took to looking into its military potential. One such researcher, Theodor Aschenbrand, published the findings of his studies in 1883, detailing how cocaine increased German soldiers' stamina and how it decreased their hunger, fear, and agitation threshold. In other words, it made them better soldiers.

These large-scale institutional inquiries into the potential cocaine led to the rapid expansion of its production in Europe, bringing the output from less than a pound to almost 160,000 lbs per year by 1885. Within two decades, the rising global interest brought about the need for mass production.

The name Dutch Cocaine Factory has an interesting ring to it, doesn’t it? As a nation known for its lean stance on psychoactive substances throughout recent history, it’s not a big stretch to imagine the Netherlands supplying the entire Old World with cocaine at some point in time.

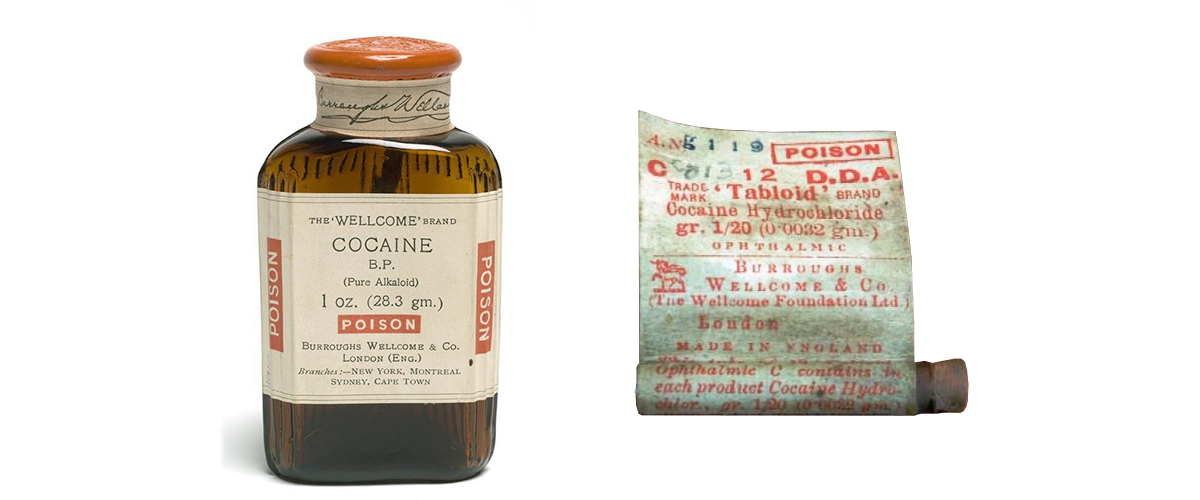

Another industry-leading producer was the British pharmaceutical giant Burroughs Welcome.

They were the first company in the world to make cocaine pills, increasing the convenience of on-the-go use, such as in battle.

During World War I, cocaine was all the rage. Soldiers on all sides used it in hopes of gaining an edge over their opponents. Unfortunately, their opponents were also on cocaine, courtesy of the Dutch. Because the Netherlands remained neutral in the conflict, their cocaine factory could churn out tons of power powder for armies of all countries. This brought the Dutch incredible economic growth, allowing them to emerge from the war thriving.

After the conflict ended, however, all of the countries which were doping their soldiers started experiencing the backlash of this practice—amidst all of the devastation the war brought, they also had to deal with thousands of veterans who were suffering from cocaine withdrawal.

The first Opium Act, which was meant to regulate substances with high addiction and abuse potential, was established in the Netherlands just after the war, in 1919. International cocaine trade was no longer legal, but Europe needed to heal, and this is how the black market of drugs started expanding.

The early 1920s were the age of the rebirth of decimated nations. The economy was booming, the culture evolving, and people reveled in the joys of newfound freedom and safety. The decadent nightlife we know of from old movies emerged in this era, affectionately referred to as “Années folles” (“Crazy Years”) by French artists.

Lavish nightclubs started popping up in cultural bastion cities such as Amsterdam, Berlin, London, and Paris. Period parties, burlesque shows, and secret cocktail bars were the name of the nightlife game, and cocaine was there to make the evenings even more golden. These good times persisted and flourished until the start of World War II.

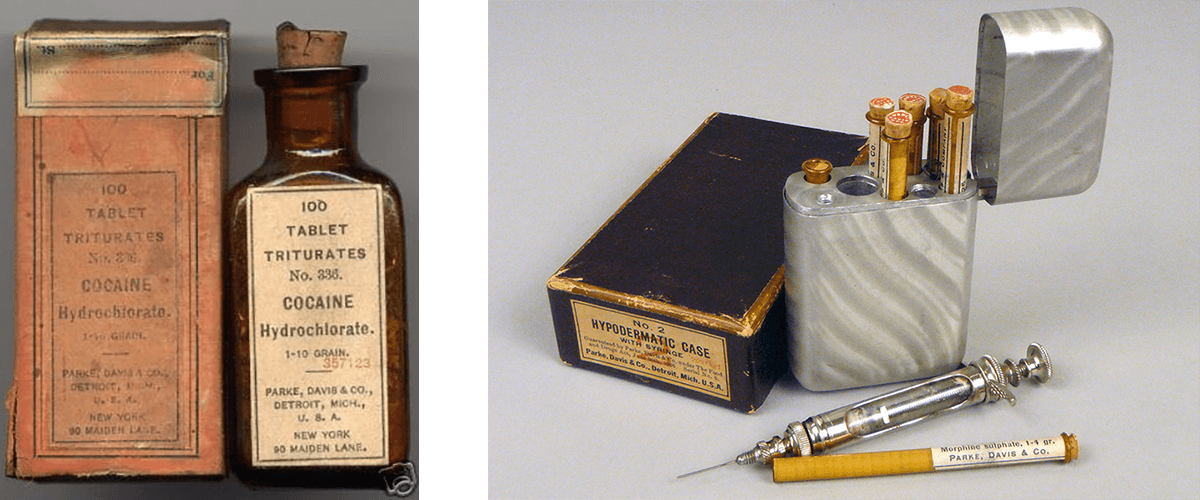

Meanwhile, in the US, the pharmaceutical company Parke Davis revolutionized the process of cocaine production, rapidly becoming the largest American supplier. In 1884, their employee, a chemist by the name of Henry Hurd Rusby, devised a way to extract crude cocaine from the coca leaves on harvest site, without having to transport them from their source. Shipping and storage were instantly simplified, yields were much more productive, prices fell, and the supply of cocaine was able to be increased substantially.

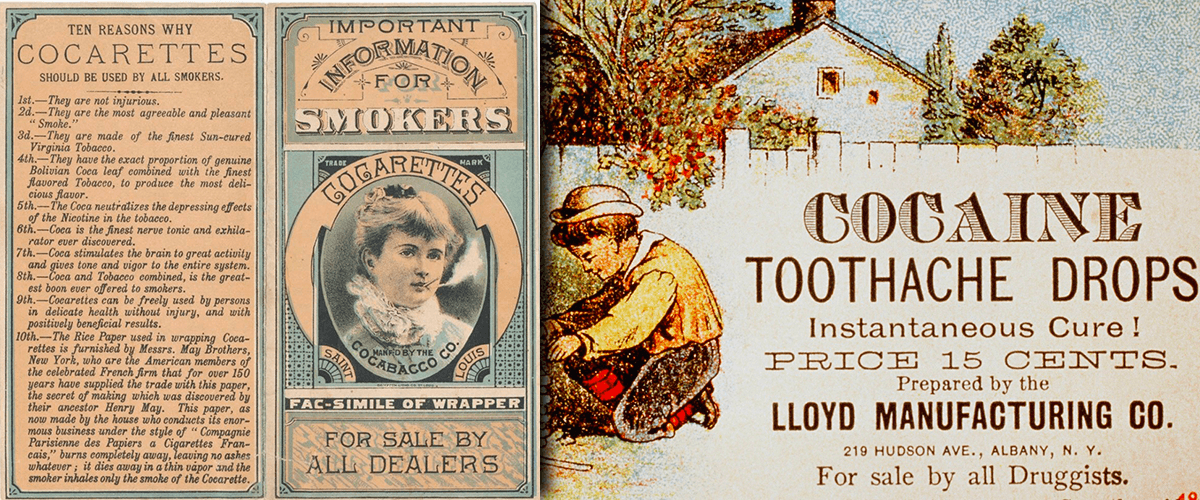

Parke Davis was selling cocaine in various forms—as powder, in cigarettes, and even as a solution which could be injected directly into the user's veins with the included needle (coincidentally, commercial production of hypodermic syringes had started up around that same time).

They marketed these products to the general public as ones that will “supply the place of food, make the coward brave, the silent eloquent and […] render the sufferer insensitive to pain.”

Unlike in Europe, in the US most of the public quickly gained almost unlimited access to cocaine. This quickly became a problem, as addictions and overdoses started occurring with worrying prevalence. On the doorstep of the 20th century, the out-of-hand US cocaine market needed to be regulated.

As with the alcohol prohibition, individual states increasingly began to curb the sale of cocaine and morphine for non-medicinal use, but they lacked the resources to enforce these laws.

The first governmental attempts to curb cocaine use came in the form of the Pure Food and Drugs Act of 1906 pablo escobar medillin cartel. This regulation required all products to list cocaine and other potentially harmful ingredients on their labels.

As the push of the individual states, on its own, proved practically powerless against drug use, a federal regulation by the name of Act was signed into action on 1914 to criminalize all non-medicinal use of addictive substances. Cocaine was pushed into the underground, and out of financial reach of most of the population.

Among the Hollywood elite, who were once again among the rare few who could afford cocaine due to the drop in supply and the tightening in regulations, its use remained a vital part of swanky social gatherings. However, with many known actors suffering from addiction and some dying from an overdose, drug use was reined in by the 1930s; not just in Hollywood, but in the entirety of the national entertainment industry.

After a good half a century on the down low, cocaine reemerged from the fringes of society, largely piggybacking on the hippie movement’s popularization of unrestrained, although not any less illegal, use of psychedelic substances. So, while hippies were dropping acid and eating mushrooms, the ‘distinguished’ were, once again, starting to indulge in the more ‘classy’ experience cocaine had to offer. As the New York Times reported in 1974, “For its devotees, cocaine epitomizes the best of the drug culture—which is to say, a good high is achieved without the forbiddingly dangerous needle and addiction of heroin, or the mind twisting wrench of LSD and the hallucinogens.”

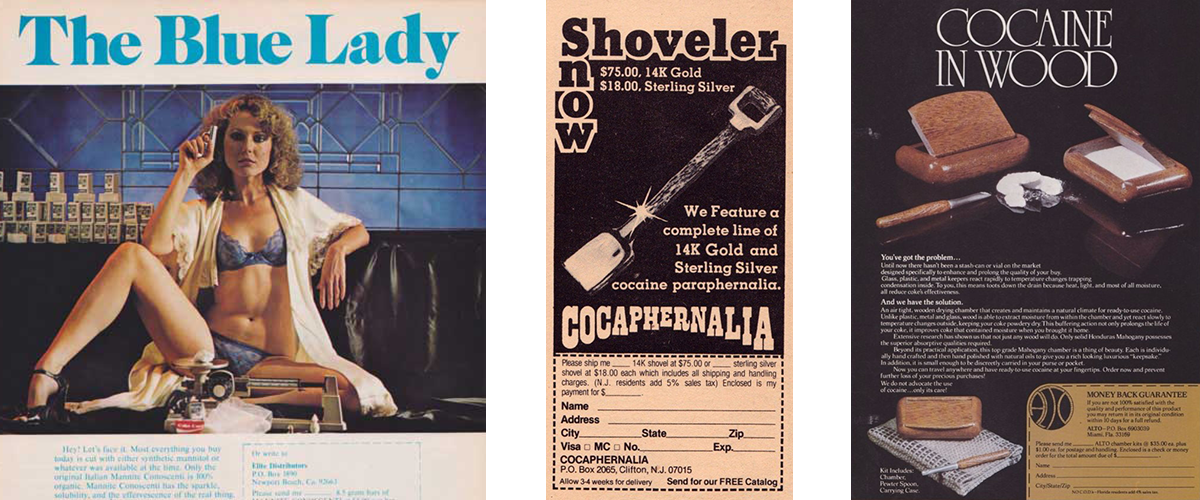

The media once again started to portray well-dressed people consuming lines of cocaine, drawing a parallel between cocaine use and the consumption of champagne and caviar by those in the most affluent strata of society.

Meanwhile, the rising demand for powder in the US was met with great enthusiasm by Pablo Escobar, the founder and leader of Colombia’s Medellín Cartel. The notorious drug trafficking organization started importing cocaine into the US at the beginning of the 1970s, eventually scaling up their infrastructure to import multiple tons of cocaine weekly.

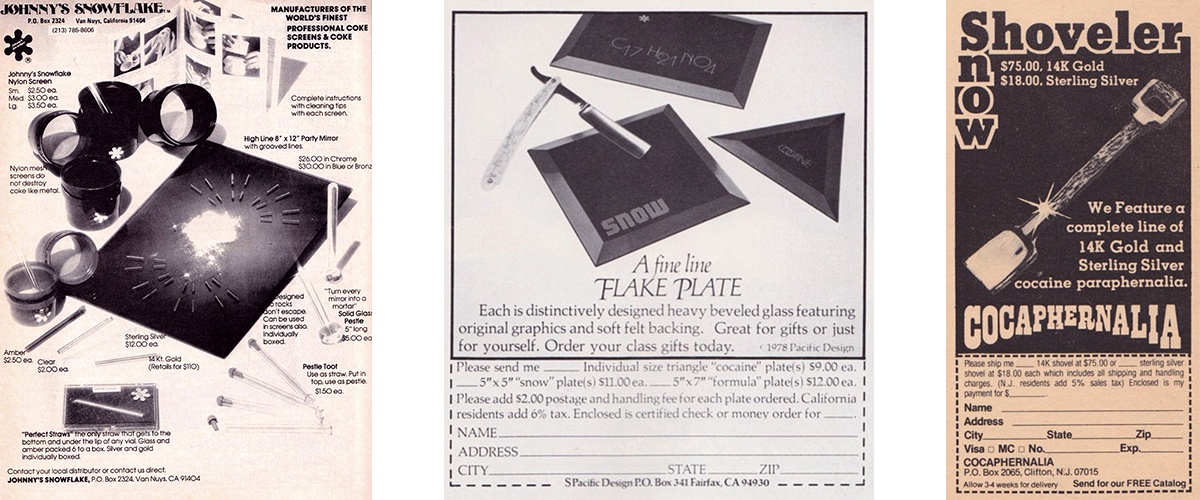

With cocaine sales booming, crafty American entrepreneurs and powder enthusiasts who weren’t willing to enter the dangerous world of crime came up with their own ways to join the industry. By designing a variety of paraphernalia to make cocaine sniffing and storing easier, classier, and more enjoyable, they were able to provide their powder lover audience with useful products while staying out of legal trouble.

While cocaine fueled the financial and entertainment industries’ outputs in the 1970s and 1980s and found its way to the tables of thousands of other affluent Americans, it was out of financial reach for most of the financially worse-off population.

This is why the emergence of crack cocaine became an instant, and unfortunate, hit with the lower class of the US population, and especially among African Americans, who staffed the majority of its distribution network.

Crack is a smokable form of cocaine made by processing the powder with sodium bicarbonate (regular baking soda) and water. Smoking crack creates a much more quick and intense high than sniffing cocaine and it’s also much more addictive than the pure powder. Lastly, it does serious damage to the body if used regularly over a long period of time.

Simple to manufacture and sold per ‘rock’ or ‘hit’ rather than per gram like cocaine, crack quickly flooded the streets of US cities. When the first crack house was discovered in Miami in 1982, it drew little national attention, with the DEA assuming it was a localized phenomenon. By 1983, however, crack appeared in New York and soon spread to other major cities. This year marked the peak of American cocaine use—over ten million people are estimated to have tried cocaine for the very first time during it. By 1985, there were more than twelve million cocaine users in America, with around a quarter of a million using daily; most of them on crack cocaine.

Ronald Reagan, the sitting president of the US at the time, took a resolute stance toward the drug epidemic and passed a series of laws to crack down hard on crack distributors. The War on Drugs, which had started with Nixon in 1971, entered a stage of aggressive suppression of drug use and dealing, and it would maintain this stance until the 2010s.

Meanwhile, Europe, which also saw a reemergence of recreational cocaine use in the 1970s and onward, did not experience a crack epidemic. Coke instead remained a steadily popular drug among underground both party-goers and the wealthy, with addiction being a relatively insignificant statistic in the big picture.

Although cocaine abuse (mostly in the form of crack) remains a problem in some Western societies, it is much less so than it was several decades ago, thanks in large part to better drug education and unlimited access to information. Recent statistics reflect a crucial decline in teenage use of cocaine and indicate that most of those who have tried cocaine nowadays are not abusers, but recreational users.

While cocaine has gotten a lot of bad press throughout its time in the Western world, the blame is not that much on cocaine, but rather on human insatiability. If an addictive treat is available in unlimited amounts, it’s a logical consequence that many will abuse it.

If kept in check, however, recreational use of cocaine, even on a relatively regular basis, has been shown in longitudinal research to not damage the cardiovascular system significantly. In other words, moderation is the key difference between using cocaine as an ally and battling it as an enemy.

This is why it’s also useful to learn about the dynamic relationship between cocaine and humans. Familiarity with all the large-scale cultural transformations this powerful alkaloid has brought about throughout history can shape our attitude toward it and create the awareness needed for safe and responsible enjoyment.

When cocaine sales were booming in the 1970s, crafty entrepreneurs and powder enthusiasts who weren’t willing to take on the risk of distribution came up with their own ways to enter the industry. By designing a variety of paraphernalia to make cocaine sniffing and storing easier, classier, and more enjoyable, they were able to provide their powder lover audience with useful products while staying out of legal trouble.

Today, after half a century, modern versions of these iconic accessories are available in an incredible variety, as are innovative new twists on tried and true products, such as the oneGee Snuff Box and the Carbon by Charly heated plate.

But also the from the 70s remaining products like a snuff bullet, coke spoon, cocaine grinder, snuff bottle, and a snuff tube.

The Elephantos online headshop stocks the largest collection of prime cocaine paraphernalia in the world. We sell only high-quality, durable accessories to ensure your snuff experiences are stylish, hygienic, and fun. Check our full selection out here.

Below you can browse our most popular products.